The Happiness of Children is a Fishy Business

We can know others by forgetting our selves.

I don’t recommend having children before marriage. It seems like common sense, but you’d be surprised how often this happens. It happened to me.

I wasn’t planning on having children so soon after college, and my 19-year-old girlfriend, now wife, wasn’t either. But in July 2008, my first daughter came into this world kicking and screaming.

The first few months were a strange, disastrous rollercoaster. She had constant ear infections for six months, and my life became a continuous trip to pediatricians' offices, pharmacies, and eventually the hospital for having tubes put in her ears. After that, everything slowed down, and I took notice of smaller aspects I had missed previously.

For example, when Madison was seven months old, I noticed she would copy my emotional state. If I smiled and laughed, she smiled and laughed. If I was sad, she was sad and cried! It was surreal, and I felt terrible for performing such an experiment. However, I had to show her mother, just once.

I thought about that exchange between baby and father for hours. How could a child with no concept of language mimic a parent's emotional state? “It must be intuition,” I thought. Next, I pondered whether animals also have this attribute.

I watched YouTube videos of gorillas and other apes mimicking the faces of humans in zoos and dogs nudging sad owners. If people and animals can intuitively deduce each other's emotional states, what does that mean? Does it mean anything at all? Is it worth pondering?

Let’s get into it.

I’m not alone in questioning this behavior. Zhuangzi, an ancient Chinese philosopher and scholar, also questioned whether it was possible to deduce someone or something else’s state of mind—he even wrote about it. Zhuangzi lived during the Warring States period, around the fifth century BCE.

Another philosopher at that time was Huizi, who enjoyed debates and logical puzzles. All of Huizi’s original work was lost to time, but Zhuangzi’s remains. As luck would have it, Zhuangzi wrote several stories regarding their interactions and friendly arguments.

Always the clown, Zhuangzi’s most famous interaction with his friend, Huizi, is whether or not Zhuangzi knew the mind of fish. Here is the story Victor Mair translated, with my minor adjustments for clarity.

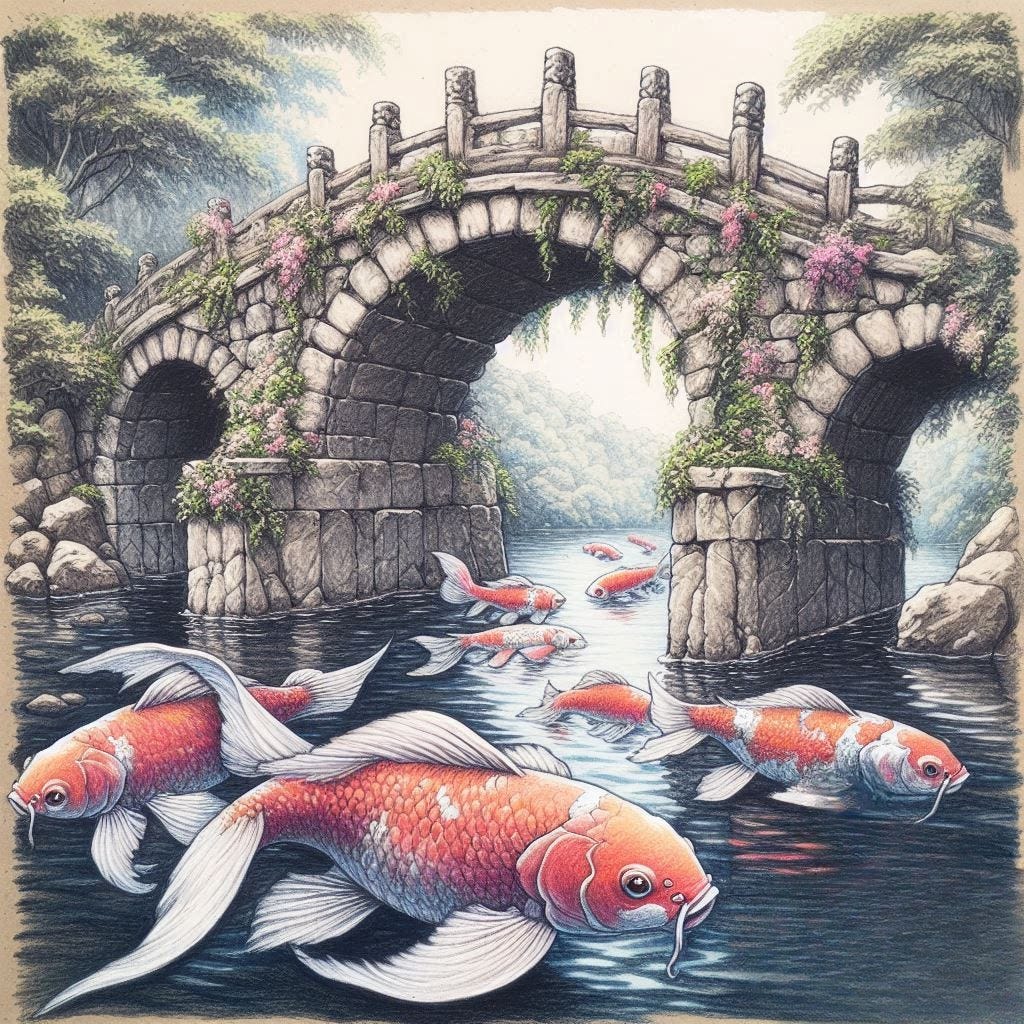

Zhuangzi and Huizi were strolling along the bridge over the Hao River. Zhuangzi said, “The minnows swim about so freely, following the openings wherever they take them. Such is the happiness of fish.”

Huizi said, “You are not a fish, so how do you know the happiness of fish?”

Zhuangzi said, “You are not I, so how do you know I don’t know the happiness of fish?”

"I'm not you", said Master Hui, "so I certainly do not know what you know. But you're certainly not a fish, so it is irrefutable that you do not know what the joy of fishes is."

"Let's go back to where we started," said Master Chuang. "When you said, 'How do you know what the joy of fishes is?' you asked me because you already knew that I knew. I know it by strolling over the Hao."

This story contains a pun and a play on words in Chinese. The pun uses the Chinese symbol ān 安, which means both "how" and "where." So, at the end of the story, Zhuangzi uses this double meaning to playfully contradict his philosophical friend. Another translation by David Jordan translates ān to “from where.”

The difference allows the pun to continue and changes Huizi’s question to, “Since you are clearly not a fish, from where do you know the joy of fish?” Zhuangzi retorts, “From where do I know the joy of fish?' From the bridge over the River Háo!" The punchline becomes a 2,500-year-old dad joke!

Beyond the pun, however, we can also analyze Zhuangzi’s answer philosophically. Remember, Madison knew I was sad simply by looking at me. She intuitively knew. Zhuangzi’s reasoning that he knows what fish feel is based on the same unspoken ability, and by placing it into words, we lose its true meaning.

This is Tao. We can not know Tao in a linguistic sense, but we can feel and sense it and allow it to flow through us. Children are masters of Tao, and as we age, we forget.

When I took my children to the park, if any other kids of any age were on the playground, they would instantly become friends, laughing, playing, telling stories, and pretending together.

There was no need for introductions, names, backgrounds, or judgments. All they cared about was that another child was playing, and they wanted to play too.

At the start of a new school year, after only the first day, my children came home with stories of new friends. I’d ask for the new friend’s name, only to be told they couldn’t remember. Names didn’t matter; actions and behaviors did. Names are created by the minds of our parents, but are not inherently real.

My parents were as likely to name me Steve or Joe as they were to name me Patrick. They could have called me Tree, Dog, or Rocking Chair, as none came from my flesh and blood. We gain names, nationalities, and religions from our parents, and while those are helpful to define our individuality, they do not flow outwardly from us naturally.

I know this is true because children don’t live this way. Kids allow Tao to flow outwardly, allowing deep personal connections to occur near instantaneously.

As adults, we intentionally reject this ability. Why? Racism, prejudice, injustice, religion, and trauma fuel our isolation and disconnectedness. These are taught to us by parents, adults, and others who have come before us.

Mistakes and problems are passed from generation to generation in an endless cycle of revenge. We lose trust in our intrinsic, natural, human connectedness through the Tao.

However, the connection is never lost, even in death, so it’s never too late to reopen our hearts and minds to the universe. As Zhuangzi stated, we already know we are connected even without words or being of the same species.

Yes, the tale is partially a joke, and Zhuangzi loves to turn Huizi’s logical arguments back around on him in several stories, but it doesn’t change the underlying message.

My daughter taught me this when she mirrored my sadness as a baby, and Zhuangzi reinforced it with his playful wisdom about fish.

Their lessons point to the same truth: we don’t need to name or define to understand. By letting go of our learned divisions, we can return to that childlike state where every encounter is an opportunity for connection, where Tao flows freely.

In those moments at the park or during a quiet evening with my kids, I’m reminded that this wisdom isn’t lost—it’s waiting. It’s in the way Madison laughs with a new friend or how she senses my mood before I speak. It’s in Zhuangzi’s grin as he teased Huizi by the river.

This unspoken bond, this flow of life, inspired a few lines that hold what I’ve learned.

If we unlearn ourselves, we learn each other. If we learn each other, we connect with Tao. If we connect with Tao, we become forever.

Do you want to encourage more learners to follow the Tao?

I’d absolutely love your support at any level that’s comfortable for you. Even if it’s only $1 per month.

$1 per month ($10/year)

$2 per month ($20/year)

$3 per month ($30/year)

$4 per month ($40/year)

$5 per month ($50/year)