Finding Peace Through Grandma's Passing

Embracing Loss with Universal Harmony

I feel lucky to have known my Grandma for as long as I did. She passed away when I was 16, and I didn’t know how to feel because the Stewart family, my dad’s side, is complicated. Even 25 years ago, I noticed something wasn’t right. We hardly ever saw each other when I was a teenager, and I could tell my mom didn’t enjoy her time there.

My brothers and I often spent the night at Grandma Stewart’s house. Some of my favorite memories of her are when we stayed up late and played games — Uno, Skip-Bo, Farkle, and Yahtzee were our favorites. Later, she bought an original Nintendo (NES) and placed it in her spare bedroom. We loved playing Super Mario Bros. 3, Excitebike, and Q*bert— a game I still don’t fully understand how to play. She would talk about dad’s family, my aunt and uncles, and tell stories of them from high school or as children. My mom’s mother, Grandma Hunt, almost never talked about her past.

As we got older, Grandma Stewart and my mom drifted apart. Years later, I found out she never liked my mom and even supported my dad’s affairs, stating, “Oh, that’s just how he is.” Something tells me that her and Grandpa had a fascinating marriage when they were young. So, as time went by and my parents' marriage began to sour, we stopped seeing my grandparents.

We still visited for the Super Bowl and Christmas, but the gifts we received were usually small trinkets—pencils, random school supplies, handmade Styrofoam Christmas ornaments (which I still have), and other small objects that didn’t require a lot of thought or effort. In fact, I used to receive a Happy Birthday phone call or maybe a card when I was a little kid, but even those stopped.

We discovered she had lung cancer due to decades of smoking, and I remember she would sit in her recliner with tissue paper in her hand. She would cough so hard that the tissue had little spots of blood on it. It wasn’t until years later that my brother told me the little spots of blood were small pieces of lung tissue.

The last memory I have of her alive is my dad coming into my room and asking if I wanted to go to the hospital to say goodbye. Looking back, I should have said yes. I wish I could have told her how much fun those years were, and I’ll always remember them, but I didn’t. I was young and still figuring out how to deal with emotions. Plus, as I mentioned, we didn’t see each other anymore, so our relationship was tattered. Her funeral was the only open casket service I’ve attended, and for good reason. It’s extraordinarily difficult to see someone you love lying there as if they are asleep. You just want them to sit up and come hang out again, but they don’t.

At the service, the pastor spoke of Grandma’s future in heaven, which I believed in then. Roads paved with gold, clouds, and praising God was about it. I remember sitting in the pew thinking, “That sounds terrible! Is that what really happens after I die?” When I went to my church’s youth group the following week, I asked my youth pastor, who affirmed my understanding. So, for decades, I thought that was it, and my Grandma was happy doing nothing besides worshiping God 24 hours a day, seven days a week, forever and ever. But I now have a different understanding of the afterlife and what my grandma is up to.

The state where I live, Texas, has a long coastline with a gulf whose name is disputed. Whenever I vacation to Galveston or South Padre Island, I love sitting on the beach and listening as the waves crash upon the sandy shore. The experience is calming, relaxing, and transcendent. Each wave forms suddenly, rolls forward, and loses itself at my feet. Then, the water, once a mighty wave, rolls backwards into the ocean only to become a wave—the cycle repeats.

If I have learned anything about Tao, it is this: everything is a cycle, and it never stops. The idea that we die and then the journey is over doesn’t make sense because nothing in the universe stops. Stars form from gas and dust, grow to incredible sizes, explode into more gas and dust, and then reform into new stars and planets. Our sun formed the exact same way as Earth, Mars, and all other planets, comets, and asteroids. Does this cycle ever end?

Scientists believe it might, but we can’t be sure because we’ve never seen it. Even if the star collapses into a black hole, Stephen Hawking showed it emits radiation (now known as Hawking Radiation) and will eventually collapse, releasing everything it’s swallowed over billions of years. That means new matter and particles to create even more stars and planets. I admit this is extremely theoretical, but by examining the Tao, we see the pattern.

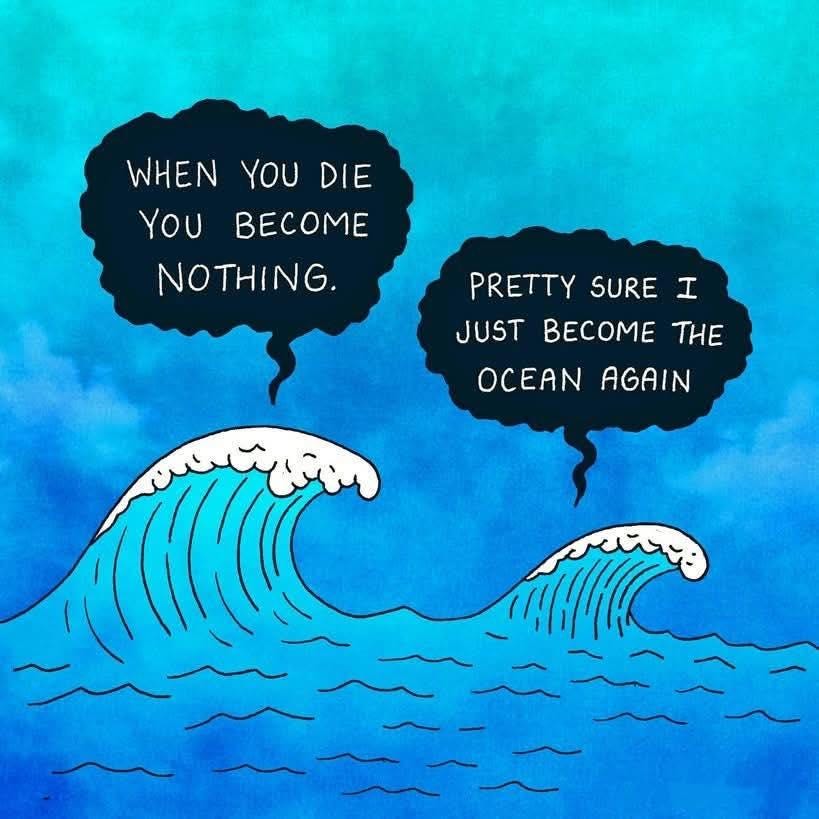

Yin and Yang can never rule each other forever. One rotates on top, but must give way to the other. Most know the yin-yang as a stationary symbol as it appears on a t-shirt or a necklace, but in reality, yin-yang can only spin, never stopping. Using the wave example from before, the ocean becomes the wave, which crashes on the shore and returns to the sea to become the wave again. I saw a meme the other day on the Taoism subreddit, which had one wave say to the other, “When you die, you become nothing.” The other wave replied, “Pretty sure I just become the ocean again.”

When I die, my body will slowly decay. The bacteria will overtake my flesh and slowly use its nutrients to sustain themselves. Then my bones will slowly become the soil and dirt, feeding plants and more animals. If my family chooses cremation, my body will be released into the atmosphere, and perhaps, some of me might escape into space if hit correctly by a neutrino. That particle could drift forever on an endless journey to a star, maybe not yet born. When collected, a new star could form, and my journey will continue forever in a cycle spanning trillions of years. Doesn’t that sound like a better forever? It does to me.

I want to become one with Tao as I was before birth. We can not have existed without not existing first. Do you remember not existing in your human body? I don’t, but others say they do. Buddhists believe we are trapped in a cycle of death and rebirth, and the goal is to escape to an eternal existence outside of this plane. I, on the other hand, believe there’s no need to escape this mortal realm.

I’m reminded of a story from Zhuangzi. Like Laozi, Zhuangzi is one of the key leaders of Taoism. Living sometime after Laozi, maybe 100 - 200 years or so, Zhuangzi wrote a collection of short stories, fables, and tall tales about his life and the world around him. Living during the Warring States period of Chinese history, a tumultuous and frighteningly violent time, Zhuangzi knew of Tao and how it could help. One particularly amusing story is the death of his wife.

Zhuangzi’s wife passed away, so his old friend Hui Zi came for a visit of condolence. When he arrived, he saw that Zhuangzi was sitting on the ground, drumming a pot and singing a song. He did not seem to be grieving, and this seemed very inappropriate to Hui Zi.

He said to Zhuangzi, “What are you doing? Your wife has been there for you all those years, raising your children and building your family with you. Now she is gone, but you feel no sadness and shed no tears. You are actually drumming and singing! Isn’t this a bit much?”

“It’s not what it looks like, my friend,” Zhuangzi said. “Of course, I was struck with grief when she passed on. How could I not be? But then, I realized that the life I thought she lost was actually not something she had originally. During all that time before her birth, she did not possess life, a physical form, or indeed anything at all. She ended up in exactly the same state, so she did not lose anything.”

“Her death was a transformation, just like when she was conceived and born.” Zhuang Zi continued. “In that state between existence and nonexistence, her initial transformation gave rise to energy. That energy gave rise to a physical form, and that physical form took on life to become a human being. Now it’s the other way around, as her continuing transformation returns her to the Tao. This whole process – from nonexistence to life, from life back to nonexistence again – is like the changing of the seasons, all completely in accordance with nature.”

“…The more I think about that,” he continued, “the more silly it seems to cry my eyes out. I will always miss her, but it is not necessary for me to grieve for her as if her death were a great tragedy.”

I love this story of Zhuangzi banging on his drum and grieving over his wife. I, too, am a drummer, and I often use drums to relieve stress or calm my anxiety. If I’m unlucky enough to outlive my wife, there will be many hours of drum banging until my hands are blistered and my tears are gone. I’ll play all day and night if I have to!

Reflecting on Grandma, I know her life is over and her body has long since decomposed, but I take comfort in knowing that even though I don’t believe in the God she did, her energy, and perhaps her spirit, live on as one with the great Tao. She simply returned to where she was for 13.8 billion years. If the universe were 24 hours old, my grandmother lived for 0.0005 seconds — a fraction of a fraction of a second on a universal scale.

I find solace in the Taoist perspective that her journey didn’t end with death but transformed into something eternal, like a wave returning to the ocean. Her energy, once vibrant in late-night card games Farkle battles, now flows within the boundless cycle of the Tao, merging with the universe. Though I regret not saying goodbye, I carry her in my memories, knowing she’s part of a cycle that never ceases.

This understanding reshapes my grief into acceptance, much like Zhuangzi’s drumming through loss. Grandma Stewart’s life, however brief in the universe’s vast timeline, was a spark that illuminated my childhood. On my next vacation to the Gulf, I’ll feel her presence in the waves’ ceaseless motion—a reminder that nothing truly ends, only transforms. Her essence, now one with the Tao, continues in every cycle, from crashing waves to distant stars, forever part of the universe’s infinite story.

Do you want to encourage more learners to follow the Tao?

I’d absolutely love your support at any level that’s comfortable for you. Even if it’s only $1 per month.

$1 per month ($10/year)

$2 per month ($20/year)

$3 per month ($30/year)

$4 per month ($40/year)

$5 per month ($50/year)

What a tender and profound piece you wrote, Patrick. Weaving together your childhood, grandmother and family dynamics, memories, death, the Tao, and even drumming.

Beautifully deep contemplative piece about longing, growing up, and growing out of our bodies.

Thank you, Patrick. 🙏✨🧿